by Troy Ellen Dixon

The critical contributions of Black women to the suffrage movement in the face of the racism that tightened its grip on the fight for the women’s vote. The tactics of white supremacy employed by white suffragists to achieve their goals.

Women’s Fight for Suffrage: Historians pinpoint the start of the Women’s Suffrage Movement as July 1848, when the Seneca Falls Convention was held to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.

From 1861 to 1865, the suffrage movement took a back seat as women focused their attention and energies toward the Civil War effort.

Following the Civil War, it became clear that Black and white women had vastly different views about why the right to vote was essential. From that point, there was an ongoing ebb and flow of “race politics.”

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper delivered a visionary speech on the relationship between the struggle for civil rights and women’s rights at the founding meeting of the American Equal Rights Association in 1866. But, as the historian Alison M. Parker has written, Harper vexed white women reformers by accusing them “of being directly complicit in the oppression of Blacks,” and demanding that they rid themselves of racism.

Feeling uncomfortable with Harper’s polished, self-assured style, which seemed antithetical to what they viewed as “Blackness,” historian Nell Irvin Painter argues that white suffragists preferred the uneducated version of Black womanhood embodied by the formerly enslaved suffragist Sojourner Truth.

The manipulation of Truth’s famous speech – the one that introduced the famous phrase “Ar’n’t I a Woman?” – by Frances Gage nearly twelve years after the Akron conference demonstrates the ingrained racism that was pervasive at the time. Gage, who supported voting rights for all, changed most of Truth’s words and falsely attributed a southern slave dialect to a woman who, it is likely, spoke English with a low Dutch accent. (For a more accurate transcription, look for the one published by Marius Robinson, who attended Truth’s speech, in the Anti‐Slavery Bugle on June 21, 1851.)

To be fair, there was some disagreement among the suffrage movement’s white leadership. Julia Ward Howe stated, “I am willing that the Negro shall get the ballot before me,” while Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton campaigned for women’s suffrage under the slogan “Woman first and Negro last.”

When Washington DC’s first suffrage parade was organized, lead planner Alice Paul expressed concern that white women would not show up if they knew they had to march alongside Black women. “As far as I can see, we must have a white procession, or a Negro procession, or no procession at all.”

This divisiveness served to exacerbate the situation and likely contributed to the ongoing disenfranchisement of Black women and men.

Undeterred, Black women continued the fight.

Some, like Mary Ann Shadd Cary, continued to work alongside white women such as Stanton and Anthony in the National Woman Suffrage Association even though its leaders “spurned any association with the cause of Black suffrage” and had adopted the stance that “educated white women were better suited to vote than illiterate Black males.”

Others, like Coralie Franklin Cook, felt a painful betrayal at the hands of women they had once idolized. Less than a year after passage of the 19th Amendment, Cook lamented that, even though she had been “born a suffragist,” she had no choice but to retire from the field because the movement had “turned its back on women of color.”

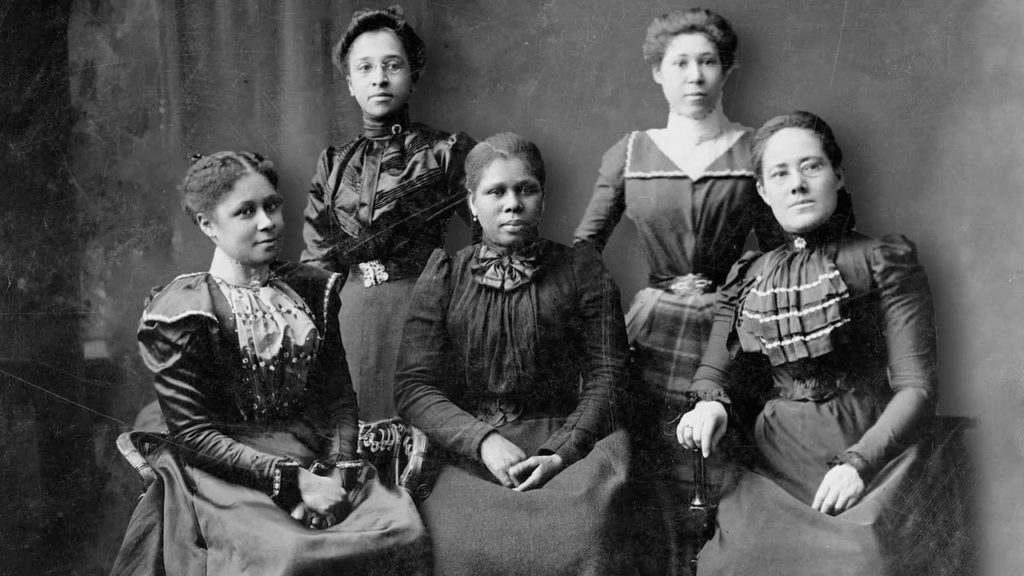

Black Women in the Suffrage Movement: Regardless of the path they chose to travel, whether born free or enslaved, these were formidable Black women whose unrelenting activism helped forge the history of this country.

Sojourner Truth became one of the most powerful advocates for human rights in the nation.

Harriet Tubman is most well-known for her efforts on the Underground Railroad.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was an early abolitionist and women’s suffrage leader.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was a vigorous member of the Massachusetts School Suffrage Association, working closely with activist Lucy Stone.

Ida B. Wells penned incendiary commentary on race relations. She fought for social equality and women’s suffrage.

Mary Church Terrell was one of the first Black women to earn a college degree and became actively involved in the women’s rights movement.

Nannie Helen Burroughs was a prominent African American educator, church leader and suffrage supporter who devoted her life to empowering Black women.

Daisy Elizabeth Adams Lampkin dedicated her life to supporting women’s rights and civil rights.

To varying degrees, each of these proud women – and so many others – experienced the attempts of white suffragists to marginalize their worth and their struggle during the fight to secure the vote for women.

Which is unfortunate because it had all started out well enough.

The Road to White Supremacy: At the Seneca Falls Convention, two hundred women came together to make the claim for full citizenship.

In their Declaration of Sentiments, they wrote “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men and women are created equal.” No caveats were attached to this statement.

Twenty-two years later, following passage of the Fifteenth Amendment – which secured voting rights for men of all races – white suffragists changed their tune.

The American Equal Rights Association splintered into two separate organizations: the National Woman Suffrage Association, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe.

In the lead-up to the Fifteen Amendment, Anthony had famously spewed, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ask for the ballot for the Negro and not for the woman.” in an 1866 meeting with Frederick Douglass.

In 1869, the following exchange between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Frederick Douglass took place during a meeting in New York City.

Stanton wondered, “Shall American statesmen…so amend their constitutions as to make their wives and mothers the political inferiors of unlettered and unwashed ditch-diggers, bootblacks, butchers and barbers, fresh from the slave plantations of the South?”

In response, Douglass remarked, “When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities; when they are dragged from their houses and hung from lampposts; when their children are torn from their arms and their brains dashed out upon the pavement; when they are objects of insult and rage at every turn…then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.”

A voice called out, “Is that not all true about Black women?”

Douglass replied, “It is true of the Black woman. But not because she is a woman. But because she is Black.”

It is no surprise that Douglass broke with Anthony and Stanton in 1870.

“You have put the ballot in the hands of your Black men, thus making them political superiors of white women. Never before in the history of the world have men made former slaves the political masters of their former mistresses.” – Anna Howard Shaw

“What will we and our daughters suffer if these degraded Black men are allowed to have the rights that would make them even worse than our Saxon fathers?” – Elizabeth Cady Stanton

“The white men, reinforced by the educated white women, could ‘snow under’ the Negro vote in every State, and the white race would maintain its supremacy.” – Laura Clay

“The old anti-slavery school says women must stand back and wait until the Negroes shall be recognized. But we say, if you will not give the whole loaf of suffrage to the entire people, give it to the most intelligent first.” – Susan B. Anthony

“White supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by women’s suffrage.” – Carrie Chapman Catt

Charitably, one may say that these white women were products of their time. Or, pragmatists.

We know that Black women were products of their life experience, which included enslavement and racism, and fighting for the survival of all Black people.

While white women were seeking the vote to achieve parity with white men, their racist rhetoric unintentionally underscored the fact that Black women were seeking the ballot as a means of empowering Black communities besieged by the reign of racial terror that erupted after Emancipation.

Once the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, white women had even less concern about the disenfranchisement that Black people would continue to face for another 45 years.

They declared the battle for women’s voting rights won and had absolutely no interest in signing on to a cause that would undercut that storyline.

The Present-Day Struggle: As Stanton and Anthony had rendered Black women nearly invisible in their influential six-volume book, “History of Woman Suffrage,” in 2019 the New York City Public Design Commission initially approved a version of history with a monument that depicted only Anthony and Stanton in the sculpture.

The outcry was immediate; and the monument, unveiled in Central Park in August 2020, was redesigned to include one of the two go-to Black women for white folks: Sojourner Truth. (The other is Harriet Tubman.)

White women advanced the cause of women’s suffrage.

Black women advanced the cause of women’s suffrage and civil rights for all Black people.

I encourage you to learn about Black Suffragists – Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Charlotte Vandine Forten, Angelina Weld Grimké, Adella Hunt Logan, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mamie Dillard, Victoria Earle Matthews, et al – so that their struggles are known, and their accomplishments are celebrated.

Black women have been at the forefront of the movement to make voting easier and more equitable since the 1800s.

With or without recognition, Black women have always been present and fighting. Black women cannot be written out of history.

Each August, I commemorate the anniversary of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which was eviscerated in a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that removed barriers to the enactment of restrictive statewide voter laws.

For Black people, the struggle against white supremacy continues.

by Troy Ellen Dixon,

published in the Kingston Wire, March 22 and March 29, 2021